Public Attitudes towards Intimate Partner Violence against Women and Influential Factors in China and Spain

[Las actitudes p├║blicas hacia la violencia de pareja contra la mujer y los factores influyentes en China y Espa├▒a]

Menglu Yang1, Ani Beybutyan2, Rocío Pina Ríos3, 4, and Miguel Ángel Soria-Verde2

1East China Normal University; 2Universitat de Barcelona, Spain; 3Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, Spain; 4Universitat Aut├▓noma de Barcelona, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2021a13

Received 9 August 2020, Accepted 10 November 2020

Abstract

Intimate partner violence against women is a social problem affecting the rights of women in different countries. The present study aimed to compare the public attitudes toward intimate partner violence against women and their influencing factors in China and Spain. A sample of 506 participants completed questionnaires related to attitudes toward intimate partner violence against women. Chinese participants demonstrated less awareness of the existence and seriousness of the issue, but more proactive attitudes than Spanish participants did. We also found that culture, gender, and age affected these attitudes directly and indirectly through gender equality attitudes. Our findings suggest that promotion of legal reforms can improve social awareness and gender equality attitudes, which in turn changes public attitudes toward intimate partner violence against women, while traditional gender roles and patriarchal society lead to cultural legitimization of the violence, resulting in remained conservative attitudes.

Resumen

La violencia de género es un problema social que afecta a los derechos fundamentales de las mujeres en distintos países. El presente estudio compara las actitudes hacia la violencia de pareja contra la mujer y los factores relacionados en China y España. Una muestra de 506 participantes cumplimentó varios cuestionarios relacionados con la actitud hacia la violencia de género contra la mujer. Los participantes chinos fueron menos conscientes de la existencia y la gravedad del problema pese a manifestar actitudes más proactivas que los españoles. También encontramos cómo la cultura, el género y la edad influían directamente en estas actitudes, e indirectamente en la actitud hacia la igualdad de género. Estos resultados sugieren que si bien las reformas legales pueden mejorar la conciencia social y las actitudes hacia la igualdad de género, que a su vez cambia las actitudes públicas hacia la violencia de pareja contra la mujer, los roles tradicionales y la sociedad patriarcal siguen manteniendo un patrón cultural violento facilitando actitudes más conservadoras.

Palabras clave

Comparaci├│n internacional, Violencia dom├ęstica, Violencia de pareja, Violencia de g├ęnero, Actitudes hacia la igualdad de g├ęneroKeywords

Cross-national comparison, Domestic violence, Intimate partner violence, Gender-based violence, Gender equality attitudesCite this article as: Yang, M., Beybutyan, A., Ríos, R. P., and Soria-Verde, M. Á. (2021). Public Attitudes towards Intimate Partner Violence against Women and Influential Factors in China and Spain. Anuario de Psicolog├şa Jur├şdica, 31(1), 101 - 108. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2021a13

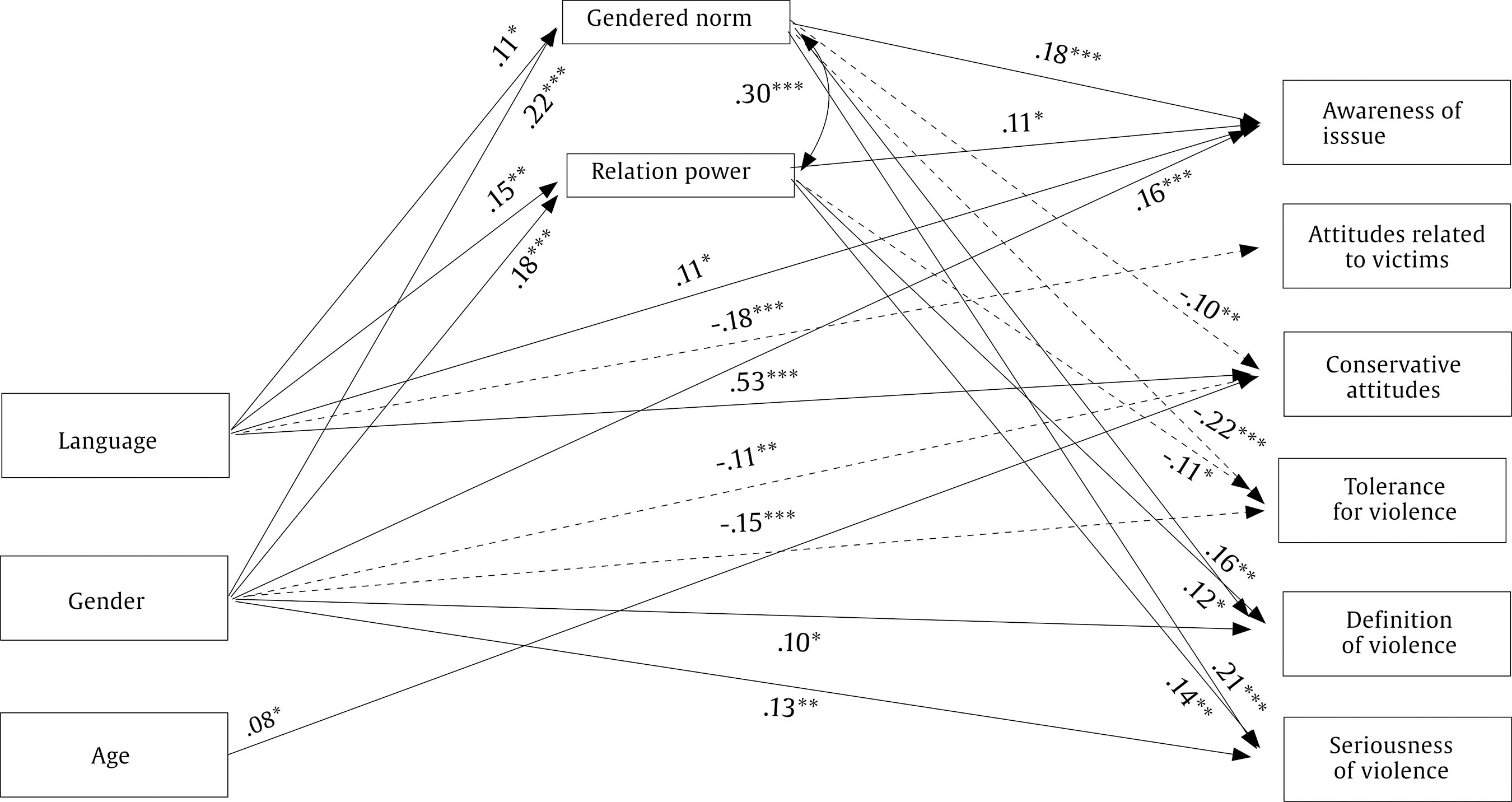

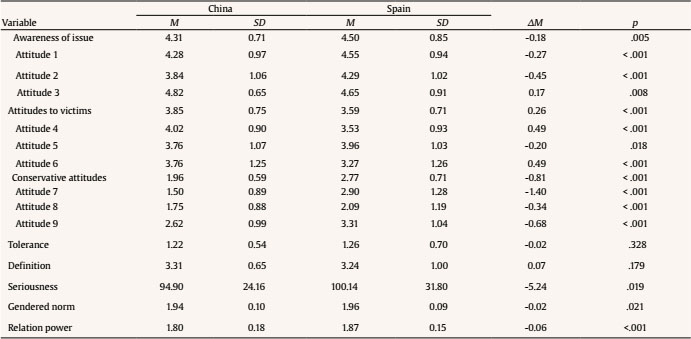

mlyang@psy.ecnu.edu.cn Correspondence: mlyang@psy.ecnu.edu.cn (M. Yang).According to United Nations (2012), between 15% and 76% women have been targeted for physical and/or sexual violence in their life-time worldwide, which makes violence against women become a serious social problem. The most common type of violence against women is violence perpetrated by a current or former intimate partner, including physical, verbal, economic, or sexual violence, which 30% of women have experienced when being in a relationship (World Health Organization, 2013). For the purpose of this article, intimate partner violence is used to define any form of physical, verbal, economic, or sexual violence perpetrated by a current or former intimate partner, a term used interchangeably in the literature with partner violence, family violence, domestic violence etc. Despite cultural, social, and economic differences, intimate partner violence against women (IPVAW) is an evident health and human rights issue across the world, which can lead to negative impact on victims’ wellbeing, such as poor sexual health, increased pain, and pharmaceutical prescription use (e.g., Cerulli et al., 2012; García-Moreno et al., 2006; Humphreys & Joseph, 2004; Moe & Bell, 2004). Besides, victims will also suffer from mental health burden, including, but not limited to, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (e.g., Lutwak, 2018). With empirical research, risk factors of IPVAW have been identified, including mental health, problem, alcohol and substance use, and unemployment (e.g., Reingle et al., 2014; Rode et al., 2015; van Wijk & de Bruijn, 2016). Although these individual factors have been showed to be related to perpetration of violence, macro-level factors explain better why women are so persistently the target (Levinson, 1989; Schechter, 1982). Feminist scholars argue that IPVAW is rooted in patriarchal culture with male dominance, in which women are considered as subordinate and dependent (Gilbert, 2002; Heise, 1998). Gender inequality and consequent power asymmetries are believed to be the driving force behind IPVAW (Campbell, 1993; Renzetti et al., 2011). In particular, those who believe in low status of women and traditional belief of gender roles would be more likely to en-gage in sexually aggressive activities (e.g., Archer, 2006; Berkel et al., 2004; Ferrer-Pérez et al., 2006; Flood & Pease, 2009; Herrero et al., 2017; Ozaki & Otis, 2017). Gender inequality exists not only in the cultural domain, but also in economic, legal, and political domains (Heise, 1994). For example, gender inequality may result in heterosexism in the justice system, victim blaming attitudes, and limited access to education and employment, (e.g., Albertín et al., 2018; Ivert et al., 2018; Korpi et al., 2013). Concerning factors from personal level to macro level, Heise (1998) proposed an ecological model in which personal, micro, and macro factors interact with each other, and specifically macro-level factors exert contextual effect on individuals. Koenig et al. (2003) further suggested that factors such as socioeconomic development and levels of overall crime will influence IPVAW both directly and indirectly through the impact on gender inequality. In addition to research on prevalence and risk factors of IPVAW (e.g., Breiding et al., 2014; Devries et al., 2013; Gracia & Herrero, 2006), researchers have also focused on IPVAW related public atti-tudes (e.g., Li et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2016; Nabors & Jasinski, 2009; Sun et al., 2012; Waltermaurer, 2012; Wu et al., 2013). Attitudes toward IPVAW have been demonstrated to play a crucial role in predicting perpetration of IPVAW, women decision making capacity, and how the community and legal enforcement respond to violence (e.g., Flood & Pease, 2006; Rodriguez et al., 2018). At individual level, researchers pointed out that attitudes toward IPVAW can be influenced by gender, socio-economic status, age etc. (Mouzos & Makkai, 2006; Taylor & Mouzos, 2006). At macro-social level, absence of legal enforcement, gender inequality, traditional gender roles, and victim blaming attitudes may result in neglecting or justifying IPVAW (e.g., Bosch-Fiol & Ferrer-Pérez, 2012; Peter & Drobnič, 2013; Zakar et al., 2013). Furthermore, even in the same region with a similar justice system, individuals from diverse cultural background would hold different attitudes regarding IPVAW, such as denial or acceptance of violence, because of the patriarchal social order of their culture (e.g., Erez, 2002; Yim, 2006). Unlike western countries where research on IPVAW has been carried on since the 1970s, Chinese researchers started focusing on such issue after the 1980s. Under Confucian influence, Chinese men have greater access to resources and decision-making power and use violence as a means for maintaining power, privilege, and control in Asian culture (Hollander, 2005). Patriarchy, which emphasizes women’s subservience to men, such as father and husband, results in the persistence of gender inequality. Over the past few years, IPVAW has surfaced as a serious public health concern due to the gendered norms and beliefs of traditional Chinese culture (Tang & Lai, 2008). In responding to greater concern about the problem, the government passed the Anti-Domestic Violence Law, which prohibits any form of violence among married couples as well as unmarried cohabitators. Since then, women suffering from violence could appeal to law. However, because of ignorance or minimization of violence reporting and limited law resources to implement actual protections, many women primarily use personal or informal resources (He & Ng, 2013; Wang, 2013; Yang et al., 2019). In addition, Chinese were more likely to believe that women should be held responsible for preventing rape, and violence could be justified in certain situations, such as a wife’s sexual infidelity (e.g., Lee et al., 2005; Yoshioka et al., 2001). Turning to Spain, despite increased social awareness of IPVAW issue, few cases of IPVAW reached a judicial decision until the issuance of Organic Law 1/2004 (Gobierno de España, 2004; Menéndez et al., 2013; Roggeband, 2012). Since then, like many other European countries, the justice system introduced several important measures which made IPVAW more visible to the public, and consequently most Spanish people consider IPVAW unacceptable in all circumstances and always punishable by law (Ferrer-Pérez & Bosch-Fiol, 2014; Orts, 2019; Schmal & Camps, 2008). Even so, the number of IPVAW increased gradually and many women still decided not to report violence in recent years (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2017; Londoño et al., 2017). Researchers also found that under the influence of honor culture, people from Mediterranean countries, Arabic countries, and Latin countries are more likely to demonstrate a traditional attitude toward gender role which leads to patriarchal society to control and discriminate women (Canto et al., 2014; Cihangir, 2013). Albertín et al. (2018) further uncovered that gender inequality in the Spanish criminal system, such as masculine sexual power and heterosexism, cause negative stereotyping of female victims. This article seeks to explore what makes people differ in attitudes toward IPVAW and how gender inequality, the important driving forces of IPVAW, affect people’ attitudes. As suggested by Heise (1994), gender inequality is related to factors in both cultural and legal domains. In response, the current study examines public attitudes toward IPVAW in two contexts, China and Spain, which have in common a male dominant culture, but differ in the legal norms related to IPVAW and recent social awareness. The first objective of this paper is then to examine cultural influence on public attitudes toward IPVAW by examining and comparing cross-cultural data from two countries. The second objective is to further explore the influence of individual and cultural factors on attitudes toward IPVAW through gender equality attitudes. Participants The total sample included 506 participants from China and Spain. Among the 255 Chinese participants (M = 25.90 years, SD = 8.38 years), 79.61% of them were female, 87.74% had education level higher than secondary school, and 45.10% had been in a stable romantic relationship with average duration of 6.39 years. Meanwhile, among the 251 Spanish participants (M = 27.35 years, SD = 10.66 years), 71.43% of them were female, 80% had education level higher than secondary school and 75.10% had been in a stable romantic relationship with average duration of 6.50 years. Instruments Attitudes toward violence against women issue. To assess the attitudes toward IPVAW, we adapted nine statements (e.g., “Violence against women is a serious issue for our community”) from the survey conducted by Taylor and Mouzos (2006). Participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). For further analysis, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis to divide these statements into factors. After comparing 1-factor, 2-factor, and 3-factor models we decided to divide the nine items into three factors: IPVAW awareness(e.g., “Violence against women is common in our community”), attitudes towards victims (e.g., “People who experience intimate partner violence are reluctant to go to the police”), and conservative attitudes (e.g., “Intimate partner violence is a private matter to be handled in the family”), which fit the data best (CFI = .971, TLI = .912, RMSEA = .087, 90% CI [0.066, 0.111]). Then, we calculated the score of each factor by averaging responses of corresponding three statements. Tolerance for violence. We used nine statements (e.g., “Admits to having sex with another man”) from Taylor and Mouzos’s (2006) survey to assess tolerance or justification for IPVAW. Participants were asked to indicate their agreement with the statements on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). We calculated the mean of the nine statements as score of tolerance. The composite reliability coefficient of the tolerance for the violence scale was .95, which supported internal consistency. Definition of violence behavior. To measure definition of violence behavior, we used another eight statements of IPVAW behavior (e.g., “If one partner in a domestic relationship slaps or pushes the other partner to cause harm or fear, is this a form of intimate partner violence?”) selected from the survey by Taylor and Mouzos (2006). Participants were asked to define whether the described behavior was IPVAW or not and to choose answer among 1 (no), 2 (yes, sometimes), 3 (yes, usually), and 4 (yes, always). After each statement, participants were also required to regard how serious the behavior was by marking among 1 (not at all serious), 2 (not that serious), 3 (quite serious), and 4 (very serious). We summed and averaged all responses of the definition to obtain the score. We also multiplied all responses of the definition by the corresponding seriousness responses and summed all scores. The coefficient of the definition of violence behavior scale was .94. Gender equality attitudes. To measure the gender equality attitudes, we administrated the scales consisting of nine items related to gendered norm (e.g., “Men need more sex than women do”) and seven relation-power items (e.g., “A woman should be able to talk openly about sex with her husband”; Underwood et al., 2014). Participants were asked to respond to each item between 1 (disagree) and 2 (agree). After reversing scores for statements that reflected gender bias, responses were summed and averaged separately to generate the scores of gender norm and relation power. A higher score on gendered norm indicates acceptance of more equitable norms. A higher score on the relation power represents more perceived agency and control in the relationship (Nanda, 2011; Stephenson et al., 2012). The composite reliability coefficient of the gender norm scale was .86 and the coefficient of the relation power scale was .71. Procedure We translated all instruments from English to Chinese and Spanish following recommended translation and back-translation procedures (International Test Commission, 2017). We recruited the participants with a push out online method by posting research information and survey link on social networking sites, such as Twitter and Facebook, which were believed to attract more diverse pool of recruits (Antoun et al., 2015). The post of the research was visible to about 30 thousand potential participants. Once entering the website of the survey, all participants were shown the informed consent that participation was totally voluntary and confidential. Only if they agreed to participate in the study voluntarily, the questionnaire would continue. Participants needed to complete several questions related to personal information, such as birth date, gender, educational level etc. After personal information section, there were four more sections related to IPVAW, including attitudes toward IPVAW, tolerance for IPVAW, and definition of IPVAW behavior, and gender equality attitudes. It took about 15 minutes to complete the whole questionnaire. Data Analyses After importing all data, we first examined the composite reliability of each scale (Raykov, 1997; see values of reliability in description of corresponding Instrument subsection). We calculated mean and standard deviation of variables and compared the differences between Chinese and Spanish participants through a t-test. Based on correlation analyses, we examined the model of attitudes toward IPVAW and the influencing factors with an estimator of maximum likelihood. Language (i.e., 1 = Chinese, 2 = Spanish), gender (i.e., 1 = male, 2 = female), age, and gender equality attitudes were examined as predictors of attitudes toward IPVAW, tolerance for IPVAW, definition, and seriousness of IPVAW behaviors. Within the model, we also examined the influence of language and gender on gender equality attitudes. Goodness-of-fit indices included comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). For quantitative data, CFI and TLI ≥ .90, and RMSEA ≤ .08 indicate acceptable fit while CFI and TLI ≥ .95, and RMSEA ≤ .06 indicate good fit (Kline, 2016). Cultural Differences of Attitudes toward IPVAW Table 1 presents means, standard deviations, and comparison of means between Chinese and Spanish participants. Chinese participants showed less awareness of IPVAW issue than Spanish participants. In particular, Chinese participants agreed less with the statements that “violence against women is a serious issue for our community” (attitude 1) and “violence against women is common in our community” (attitude 2), but agreed more with the statement that “intimate partner violence is a criminal offence” (attitude 3). With respect to attitudes related to victims, Chinese participants were less likely to understand the situation of victims than Spanish participants. For example, Chinese participants agreed more with “people who experience intimate partner violence are reluctant to go to the police” (attitude 4) and “it’s hard to understand why women stay in violent relationships” (attitude 6), but disagreed with “most people ignore intimate partner violence” (attitude 5). However, Chinese participants demonstrated a less conservative attitude toward IPVAW than Spanish participants. For instance, Chinese participants were less likely to agree with “intimate partner violence is a private matter to be handled in the family” (attitude 7), “intimate partner violence rarely happens in wealthy neighborhoods” (attitude 8), and “police now respond more quickly to IPVAW calls than they did in the past” (attitude 9). There were no statistically significant differences in tolerance for IPVAW and definition of IPVAW behavior between Chinese and Spanish participants. However, Chinese participants rated IPVAW behaviors less serious than Spanish participants. Turning to gender equality attitudes, Chinese participants showed slightly less acceptance of equitable norms and lower relation power than Spanish participants. Influencing Factors of Attitudes toward IPVAW Model of attitudes and the influencing factors fit data well (CFI = .999, TLI = .988, RMSEA = .031, 90% CI [0.000, 0.087]). As shown in Figure 1, both language and gender positively predicted gendered norm and relation power which were positively correlated with each other. Gendered norm positively predicted awareness of IPVAW issue, definition of IPVAW behaviors, and seriousness of IPVAW behaviors, but negatively predicted conservative attitudes and tolerance for IPVAW. Relation power was found to positively predict awareness of IPVAW issue, definition of IPVAW behaviors, and seriousness of IPVAW behaviors, and to negatively predict tolerance for IPVAW. Moreover, language positively predicted awareness of the issue, conservative attitude, and negatively predicted attitude related to victims. Gender was found to be a positive predictor of awareness of the issue, definition of IPVAW behaviors, and seriousness of IPVAW behaviors, but also to be a negative predictor of a conservative attitude and tolerance for IPVAW. Age was only found to be significantly a positive predictor of conservative attitudes. Figure 1 Model of Attitudes toward IPVAW and Influencing Factors.   Note. Only paths of significant effect were showed in the figure. Dashed lines depict negative regression. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001 With the objective to explore how people differ in attitudes toward IPVAW, the present study provides empirical results of individual and cultural factors influencing attitudes through gender inequality. We found that Chinese participants demonstrated less awareness of the existence and seriousness of IPVAW than Spanish participants. We also found the direct impact of culture, gender, and age on attitudes toward IPVAW, and the indirect impact of culture and gender through gender equality attitudes. Both Chinese and Spanish participants presented little tolerance for IPVAW and defined most offensive conduct as IPVAW. Nevertheless, similar to the results of comparative studies conducted in China and the US (Li et al., 2017), Chinese participants were less aware of the existence of violence and situation of victims and considered violence behaviors less serious than Spanish participants. Such difference may be explained by more news report and related legal enforcement in Spain (Menéndez et al., 2013). Spanish participants tended to hold more conservative and traditional attitudes, such as “IPVAW is a private issue rather than crime”. This finding implies that in spite of the occurrence of encouraging political and social changes in countries like Spain, violent behaviors in domestic contexts would remain culturally legitimized, which results from persisting beliefs about women’s role in relationships (Albertín et al., 2018; Allen & Devitt, 2012; Alves et al., 2019; García-Moreno et al., 2006; Kimuna et al., 2012; Yamawaki et al., 2012). The cultural and cognitive legacy of women’s submission to male figures and gender inequality throughout history often become social values and traditions that frequently lead to the justification or tolerance of male violence (Bosch-Fiol & Ferrer-Pérez, 2012; Esqueda & Harrison, 2005; Jankowski et al., 2011; Knickmeyer et al., 2010; Korpi et al., 2013; Peter & Drobnič, 2013; Valor-Segura et al., 2011; Worden & Carlson, 2005). In addition to the cultural influence, individual factors were also found to be related to attitudes toward IPVAW. Female participants were more aware of IPVAW issue, expressed more understanding to the situations of victims, held more proactive attitudes toward IPVAW, presented less tolerance for violence, and defined more behaviors as serious violence. The encountered gender influence of attitude toward IPVAW was consistent with previous findings that women presented positive attitudes toward IPVAW, showed more knowledge about IPVAW, and rated IPVAW more serious than men (Alazmi et al., 2011; Locke & Richman, 1999; Sorenson & Thomas, 2009). Such gender difference of attitudes toward IPVAW may be explained by difference severity of impact on men and women. Although both men and women can be victims of violence during a relationship, women are likely to suffer greater injury, fear, and other negative physical and psychological outcomes of violence during the relationship (Romito & Grassi, 2007; Whitaker et al., 2007; Williams & Frieze, 2005). This is because the violence perpetrated by a woman against a male is believed to be situational violence related to the family conflict and external stressors while violence perpetrated by a man against women occurs when a man uses violence as power to dominate a woman, which results in more serious consequences (Archer, 2000; Ferrer-Pérez & Bosch-Fiol, 2019). Therefore, most males consider IPVAW as an issue which would not affect them and consequently pay less attention to IPVAW. Besides, young participants were less likely to hold conservative attitudes toward IPVAW which has also been found in previous studies (e.g., Bryant & Spenser, 2003). As for gender equality attitudes, we found that people with more gender equitable attitudes presented more awareness, more proactive attitudes, less tolerance, as well as broader definition of serious violence behaviors. A similar relationship has been found between gender equality attitudes and prevalence of IPVAW in previous studies (e.g., Grabe et al., 2015; Heise & Kotsadam, 2015; Lasley & Durtschj, 2016; LeSuer, 2019; Zapata-Calvente et al., 2019). Stalans and Finn (2006) further uncovered that people who disfavor male-dominant relationships are more likely to believe that husbands’ use of violence is intentional and unjustifiable. Researchers also suggested that improving gender equality attitudes could help people develop a more positive attitude toward IPVAW (Yilmaz, 2018). Furthermore, gender equality attitudes, both gendered norms and relation power, were found to be influenced by culture and gender. For example, Chinese participants showed less acceptance of equitable norm and lower relation power than Spanish participants. As indicated by Fischer and Manstead (2000), gender empowerment was highly related to individualism. Compared to Spain, China is considered as an extremely collectivistic country with lower societal power for women (Hofstede & Arrindell, 1998; Yick, 2001). Especially the Confucian culture, rooted in the Chinese community, emphasizes women’s subservience to men (Niu & Laidler, 2015). Consistent with the results from other Asian countries, that belief of traditional gender role from patriarchal culture can affect attitudes toward IPVAW (Zakar et al., 2013), the inequitable gender norm, and relation power in China also remain influencing people’s attitudes. Limitations and Future Investigation In the current study we encountered a cultural influence on attitudes toward IPVAW, which may arise from traditional gendered culture and justice system. In order to clarify the contextual effect in different domains, further examination of factors related to justice system is needed. For example, Chinese people are believed to present little support to law enforcement and high rejection of police intervention because of the belief that “the law should not step in home” (Sun et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2013). Thus, we recommend assessing attitudes toward police reaction or justice system which are highly associated with attitudes toward IPVAW (Sun et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2012). Though we found an impact of individual and macro factors on attitudes toward IPVAW, factors at other levels, such as community and household levels (Koenig et al., 2003), will need to be addressed in future investigation to build and extend the model. In the current study, we used social networking media to recruit participants online which resulted in a limited variety and inequivalence of the sample. For example, most participants obtained at least Bachelor’s degree or junior college diploma, and as a result we were unable to encounter the influence of the education level on attitudes. In addition, due to the limited diversity, our results may not be generalized to the whole society, especially to rural regions with low education level, where the IPVAW have been found to occur more frequently and people are more likely to hold traditional and negative attitudes (e.g., Niu & Laidler, 2015). When administering the questionnaires, we also noticed that we received rejection mostly from men, which results in fewer male participants. On one side, such inequivalence of the samples implies that men show less interest and pay less attention to the IPVAW issue, which is consistent with our findings. On the other side, the inequivalent sample also limited the generalization of our results. For instance, men who decided to participate in the study already showed positive attitudes to the issue compared with those who rejected to participate. Regarding the limited samples, our findings only provide a brief insight into how people view IPVAW and demonstrate a gradual change of public attitudes held in China and Spain. In future studies, we need to collect more opinions from various groups of population, especially those coming from rural regions and tend to hold conservative and negative attitudes toward to the issue, by conducting face-to-face research with samples from different background. As the most prevalent type of violence against women, IPVAW has drawn more and more social and scientific attention. Researchers suggest that intimate partner violence can be divided into situational violence, which is related to family conflict and stressors, and coercive control violence, which is related to male dominance and gender inequality (Johnson 1995; Kelly & Johnson, 2008). Although intimate partner violence can also be perpetrated by a woman against a male, such a violence is more likely to be situational violence. On the contrary, IPVAW is a type of violence based on gender which can lead to much more serious consequences (Archer, 2000). Therefore, researchers highlight the importance of a gender perspective when conducting research on IPVAW (e.g., Barón, 2019; Delgado-Álvarez, 2020; Ferrer-Peréz & Bosch-Fiol, 2019). In the current study, we adopted feminist theories to examine people’s attitudes toward IPVAW and used gender equality attitudes as an important gender-related variable to explore how people’s attitudes differ. The current study is consistent with the ecological model of IPVAW risk factors (Heise, 1998). We found the impact of individual and macro factors on attitudes toward IPVAW. The cultural influence on attitudes toward IPVAW, which may come from both traditional gendered belief and justice system, results in Chinese participants demonstrating less awareness of the existence and seriousness, but more proactive attitudes. As suggested by Heise (1994), impact of risk factors on prevalence of IPVAW functions in both cultural and legal domains. Our findings reveal that despite the promotion of legal reforms, culture of traditional gender role still has influence on public attitudes. However, we have to recognize that online recruitment limited the generalization of our findings to rural and low-income regions, where people have restricted access to the internet. According to feminist scholars, gender inequality is a driving force of IPVAW at macro level. In line with Koenig et al. (2003), we also found both individual and macro factors can affect attitudes toward IPVAW indirectly through gender equality attitudes. For instance, gendered norms and relation power, the predictor of attitudes toward IPVAW, were found to be influenced by culture and gender. These results highlight the importance to enhance public attitudes toward IPVAW through education on gender equality targeted for different culture and gender. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Yang, M., Beybutyan, A., Pina Ríos, R., & Soria-Verde, M.A. (2021). Public attitudes towards intimate partner violence against women and influential factors in China and Spain. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 31, 101-108. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2021a13 References |

Cite this article as: Yang, M., Beybutyan, A., Ríos, R. P., and Soria-Verde, M. Á. (2021). Public Attitudes towards Intimate Partner Violence against Women and Influential Factors in China and Spain. Anuario de Psicolog├şa Jur├şdica, 31(1), 101 - 108. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2021a13

mlyang@psy.ecnu.edu.cn Correspondence: mlyang@psy.ecnu.edu.cn (M. Yang).Copyright © 2025. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS